BuzzFeed News; Getty Images

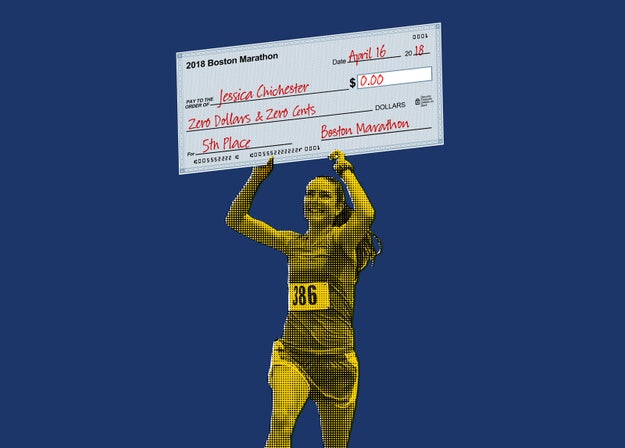

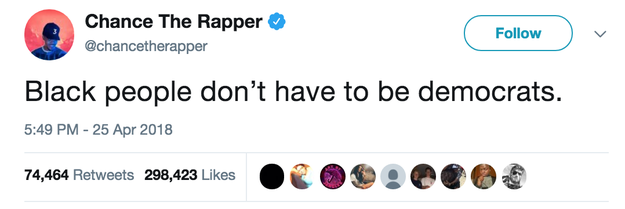

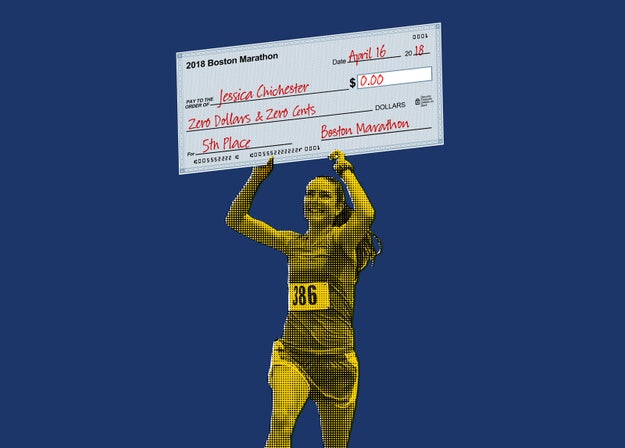

When Jessica Chichester crossed the finish line of the Boston Marathon earlier this month, she had no idea she'd just placed fifth among the women racing.

It was a miserable day for a race, with sideways rain and some of the lowest temperatures for April 16 in decades. But after 18 weeks of rigorous training, the 31-year-old nurse practitioner had endured.

"It was just like a fierce battle the whole time, plowing through 30 mile-per-hour headwinds and rain and dodging puddles," Chichester, who leads the New York running team the Dashing Whippets, told BuzzFeed News.

After the race, she checked her phone and found a flood of texts from loved ones telling her she'd finished with the fifth fastest time for a woman running. Chichester couldn't believe it — she even wondered if it could be an error.

The prize for both male and female fifth place winners in the Boston Marathon is $15,000.

But, unlike the male runner with the fifth fastest time, Chichester didn't walk away from the race a penny richer.

Why? Because there are different rules for men and women running the race.

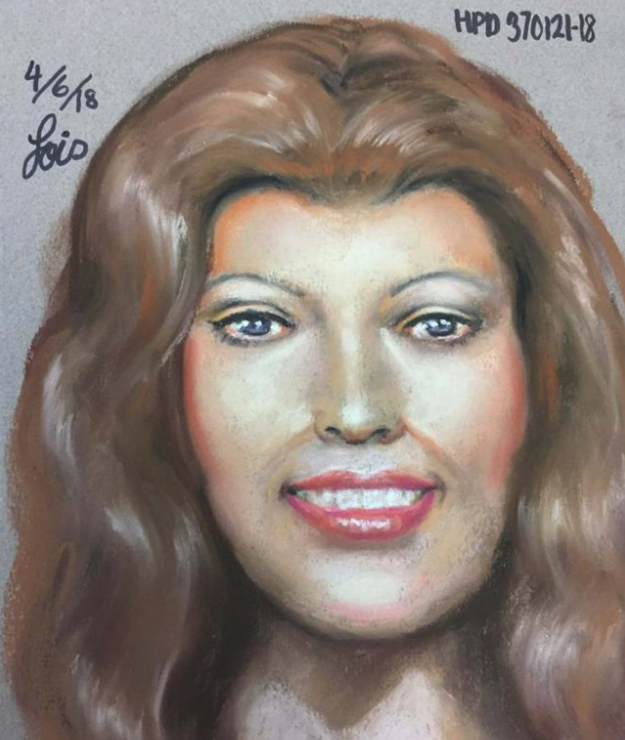

Jessica Chichester

MarathonFoto

To be eligible for prize money as a female Boston Marathon runner, you must first qualify for the Elite Women's Start (EWS), a professional-level starting group which requires the highest level of marathon times.

The exact qualifying time for the EWS varies year to year, but was 2:47:50 this year, said T.K. Skenderian, communications director for the Boston Athletic Association, which organizes the race. Just 46 women made the cut.

This group starts 28 minutes earlier than the rest of the marathoners, but winners are decided based on overall times, rather than who crosses the finish line first.

No similar division exists for elite male runners — so, if you place up to fifteenth in the Boston Marathon as a man, you'll win money no matter what.

This means 16,587 men were potentially eligible for a cash prize this year, compared to just 46 women.

Skenderian told BuzzFeed News the EWS, which began in 2004, is designed "to highlight head-to-head racing and competition."

"As opposed to starting men and women at the same time, and ultimately having the female competitors lose each other among packs of men (and potentially receive pacing assistance), the EWS allows athletes to compete without obstruction," said Skenderian.

The EWS "gives the fastest women the chance to race each other openly" and "allows the women’s race to get more tv coverage," said Skenderian.

According to the marathon's website, female runners must email organizers in advance to determine if their qualifying time is fast enough to be eligible for the EWS. If women don't start with the EWS, but still race, they "waive the right to compete for prize money."

"Eligible athletes [for the EWS] can make an informed choice to seek prize money or not to seek prize money," said Skenderian.

When asked how the Boston Athletic Association feels about women who don't qualify for the EWS yet still finish in the top 15, Skenderian said they are "very happy for any woman who finishes in the top 15 net times."

Brian Snyder / Reuters

Chichester hadn't been allowed to join the EWS, having just missed the qualifying time.

But on the day of the race, she ran it in 2:45:23 — just 23 seconds above Olympic marathon qualifying time.

Her brother had a similar "breakthrough race" in 2012, where he unexpectedly placed eleventh in the marathon. He was awarded the prize money, despite not running with the men's elite division, she said.

"It makes me sad that there’s not a way for people that are in the mass-start, that have a breakthrough race and come up from having not as good of a time, can be eligible for the prize money they deserve," said Chichester.

She drove back home to Brooklyn that night, and worked a 10-hour shift the following day.

Female runners who don't qualify for the EWS don't usually wind up in the top 15, but the 2018 Boston Marathon wasn't a usual race.

The poor weather conditions led to the slowest winning times since the 1970s, and 50% more people dropped out of the race than they did last year, according to the New York Times.

Still, these dropout rates weren't equal across genders — 5% of men quit the race, compared to only 3.8% of women. The men's dropout rate rose 80% over last year, while the women's dropout rate went up just 12%.

Chichester wasn't the only female Boston Marathon runner that left without prize money they might have otherwise received.

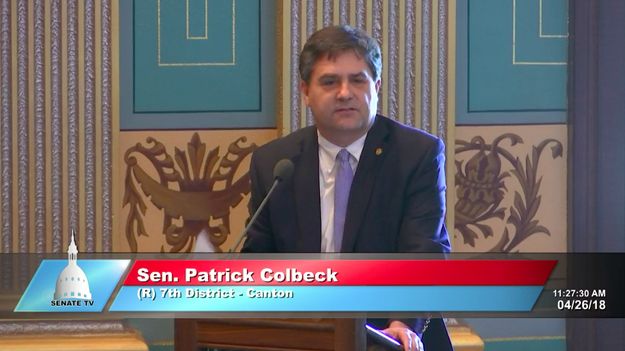

Veronica Jackson

MarathonFoto

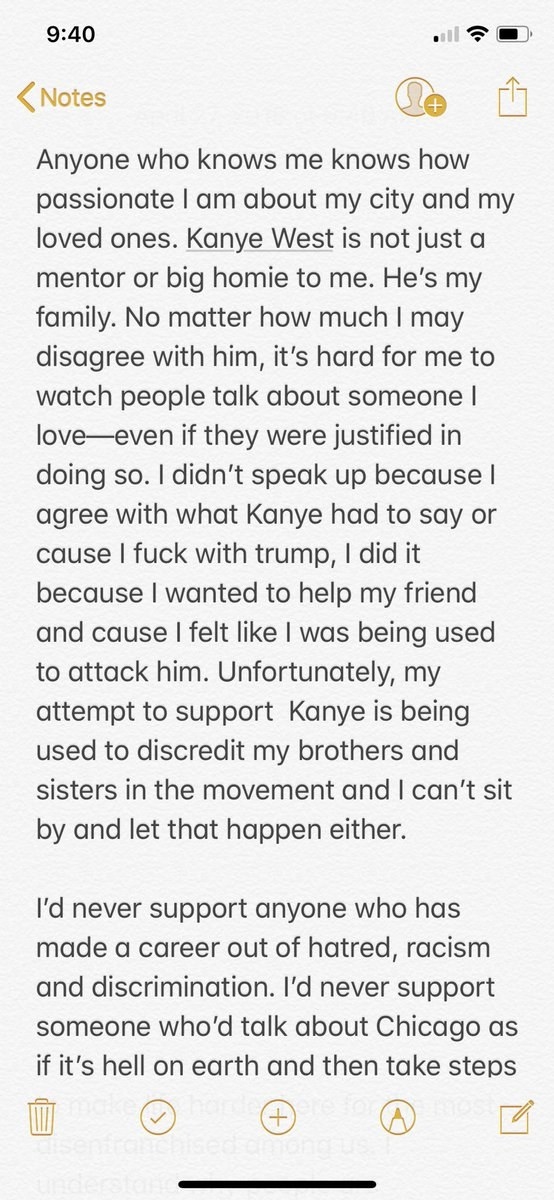

Veronica Jackson, 31, also missed the cutoff to qualify for EWS. But, when she saw how the weather was looking on race day, she set a higher than usual goal for herself.

"I can run in the elements pretty well, so I knew when the weather was looking bad, I actually set a goal for myself to be top 20 or top 25," Jackson told BuzzFeed News.

She wound up getting thirteenth place — usually worth a $1,800 prize.

Of course, she, too, was not awarded the money.

"The men who are in my position are often called sub-elite, and they’re a group of people who are not quite in the professional [elite] group," said Jackson, calling the situation "frustrating."

"In races, men’s sub-elites get to start with the elite men. Women’s sub-elites don’t," she said. "Men’s sub-elites are always eligible for prize money. Women's sub-elites are not. And that’s really unfair."

Boston isn't the only marathon with a rule like this. In the New York City Marathon, "only women competing in the all-women’s professional race are eligible for Open Division prize money," according to the website.

"If they were to say you have to be in the elite field to get the money, then they need to allow more runners in this elite field," said Jackson. "You know, I wanted to be in it."

Even though Jackson counts the Boston Marathon as "favorite race in the world," that $1,800 would have meant a lot to her, she said.

"That would cover a lot of race expenses," she said. "And I’m getting married this summer, so some of it would’ve gone there."

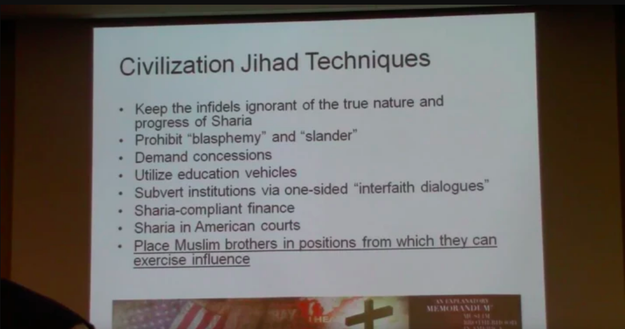

Becky Snelson

MarathonFoto

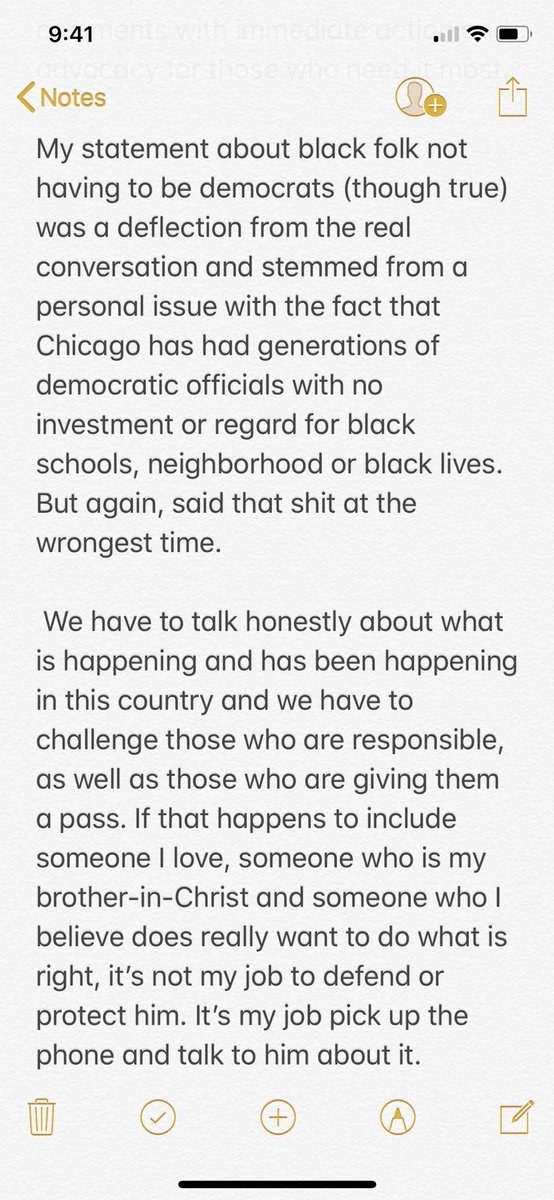

Becky Snelson, 24, placed fourteenth at the Boston Marathon this year, having also not been offered a spot on the EWS. The prize for placing fourteenth is $1,700.

"When I crossed the finish line, I’d been tracking my time on my watch and I knew that I’d gotten the time that I wanted, so I was elated," Snelson said. "And I was immediately very concerned about when I was getting that heat blanket because I started getting very cold once I was done."

She was shocked when she found her mom and was told how she'd placed.

"I was sort of in disbelief, and I'm still sort of in disbelief about it," Snelson said. "I came in fourteenth at a World Marathon Majors. I didn’t even know that was on my bucket list, but now I did it."

If she'd been given the $1,700 prize, Snelson said she would've used it to help pay off her student loans.

"It’s definitely a unique situation, because the men that start not in the elite men’s start, they’re still allowed to qualify [for prize money]," she said.

After an extraordinary race, Snelson's trying her best not to let it bother her — but, she said, "it kind of stinks a bit."

"I earned this money because I was the fourteenth fastest that day," Snelson said. "I didn’t expect to walk out of Boston making money either, but I feel like I kind of deserve it."

from BuzzFeed - USNews https://ift.tt/2HVdSJX